Ancestors who Enslaved People

In my ancestors’ wills, enslaved human beings are listed as property, bequeathed to wives and children alongside money, land, livestock, tools, and beds. The first document I turned up along these lines, more than a decade ago, was signed January 15, 1816, by my fifth great-grandfather, Davis McGee, an ancestor through my father’s mother’s dad. Davis was born in Somerset, Maryland in 1846, married Penelope Shockley, migrated to the middle of Georgia at some point before or after their union, and died there in 1817.

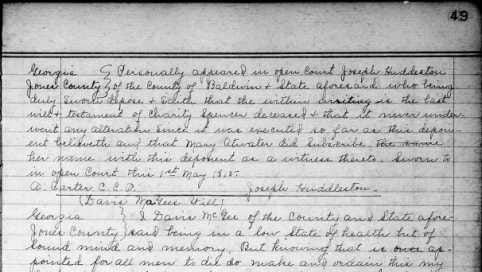

“I give and bequeath until my beloved wife Nelly McGee my land Household and kitchen furniture, and also my Negroes,” Davis directed (capitalization and punctuation in the original, above), “to wit: Grace, Sall, Mary, Pat, Stephen, and Nemrod, and all my stock and plantation tools, that is to say my estate both real and personal during her natural life or widowhood.”

At Nelly’s death, all of these people and this property was to pass to his namesake, the younger Davis McGee, except that his eldest daughter, Charlotte, would become the legal enslaver of Mary at that time, and another of his sons, Richard, would take charge of Nemrod’s bondage. Davis’ six other children, including my fourth great-grandfather, Joseph, were each to receive one dollar.

When the will was probated in February 1817, the estate – including Grace, Sall, Mary, Pat, Stephen, and Nemrod -- was valued at $5,348, or $101,215 in today’s dollars. According to a number of family trees on Ancestry.com, Davis’ wife Nelly died in 1816, after the will was written but before Davis succumbed the same year. I haven’t been able to confirm this. If it’s true, Davis McGee, Jr. took possession of the whole estate, stepping directly into the shoes of enslaver, at his father’s death.

By the time of the 1850 census, the younger Davis McGee enslaved fifty people ranging in age from four months to 75 years old, on land 23 miles from Selma, Alabama. At one point, he ran a “stagecoach inn,” where “travelers could stop-over for food and lodging and horse traders from Tennessee could congregate to sell or swap their stock,” according to a nostalgic 20th century brochure distributed by a local bank.

Many of us know of Selma because, more than a century later, in 1965, it was still a white supremacist capital. The legacy of my enslaving ancestors endured then and continues now.

While my fourth great-grandfather, Joseph McGee, was not granted ownership of human beings through his father’s estate, Joseph enslaved twelve people before he died all the same.

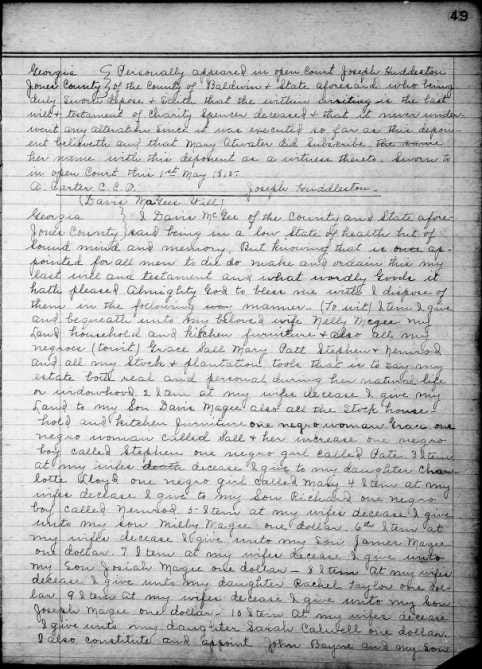

Joseph’s will (above) was written in November 1850, the month after his wife, Susan, died, in Holmes County, Mississippi. It directs that all his “land, stock, and property of every description except my negroes be sold,” and that his youngest unmarried daughter, my third great-grandmother, Sarah Ann (Sallie) McGee, then 16, should receive “a bed stead and all necessary furniture in addition to her distributive share of my estate.” He goes on to provide that:

the residue of my property consisting of the following negroes and their increase viz Burwell and Joan, Bob, Martha, Esther, Buddy, Ralph, Alfred, Randle, Kat, Burwell and Jim be divided into seven lots, Burwell and Joan constitute one lot so they not be separated and divided by lot among my seven children.... the division to be made by five disinterested men in such manner as for all to be made equal. In the event that my daughter, Sarah Ann McGee [my third great-grandmother again], shall be single at the time of such division, I will that she have the choice of the lots so made.

As I’ve said on Twitter, when I started researching my family history, I expected to find that at least a couple of my ancestors enslaved human beings. Now I keep losing count of how many did and how many humans they enslaved.

My father was an overt white supremacist. Over the years, I’ve sometimes felt that people who cared about me, friends and teachers, editors and mentors, viewed my preoccupation with all of this history as an unfortunate byproduct of my racist childhood, a sort of lingering racist imprint on my own brain.

Growing up the way I did made it impossible for me to ignore slavery. Reckoning with the metastasis of my ancestors’ wrongs is a lifelong project for me. Doing that in public feels right.

It’s been longer than expected since my last dispatch, and my book draft and day job continue to demand almost all my writing attention, but I’ll be back in touch when I can.

All good wishes until next time,

Maud