Emotional recurrences in families have fascinated me as long as I can remember. As I explain in Ancestor Trouble, “the more I feed my fixations, the sooner they tend to wither, but this one tends to permeate my perception of humanity. I often think family patterns are the primary existential conundrum we all have in common, apart from death and basic needs like food and shelter—but, then, questions of sustenance and longevity are intensely tangled up with our ancestors, too.” Nothing energizes me more than pondering the layered, wide-ranging implications of kinship and how family echoes bubble up in uncanny synchronicities and some of the most deeply resonant art. It’s in that spirit that I’m returning to my earliest online impulses, writing once a month or so about writers and their books as they (in my mind, at least) connect to these preoccupations.

I’ve been reading Emily Raboteau since her novel, The Professor’s Daugher, appeared in 2005. Her second book, Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora, is one I’ve turned to repeatedly over the years, from the time I mentioned it in my New York Times Magazine mini-column shortly after the book’s publication in 2013, through all the years I worked on Ancestor Trouble. In the first chapter, Raboteau describes an interrogation and strip search by El-Al security personnel on a trip to Israel. Asked for answers about the origins of her middle name that she couldn’t give because of slavery, she writes that she “had never felt more black than when I was mistaken for an Arab.” We’ve all become conversant in ideas about emotional inheritance and intergenerational trauma in recent years, but Raboteau articulated these thoughts and feelings eleven years ago:

I inherited my sense of displacement from my father. It had something to do with the legacy of our slave past. Our ancestors did not come to this country freely... But it had even more to do with the particular circumstances of my grandfather's death. He was murdered in the state of Mississippi in 1943. Afterward, my grandmother, Mabel, fled north with her children, in search, like so many blacks who left the South, of the Promised Land. It was as if my father, whose father had been ripped from him, had been exiled. My father's feelings of homelessness, which I took on like a gene for being left handed, were therefore historical and personal. And truthfully, because he left my family when I was sixteen, my estrangement had also to do with the loss of him. My family was broken, and outside of its context, I didn't belong.

In a recent interview, Raboteau says the question at the heart of Searching for Zion “is a young person’s question: Where do I belong?” By contrast, her third book, Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “The Apocalypse”, focuses on a more urgent question: “What can I do to help?”

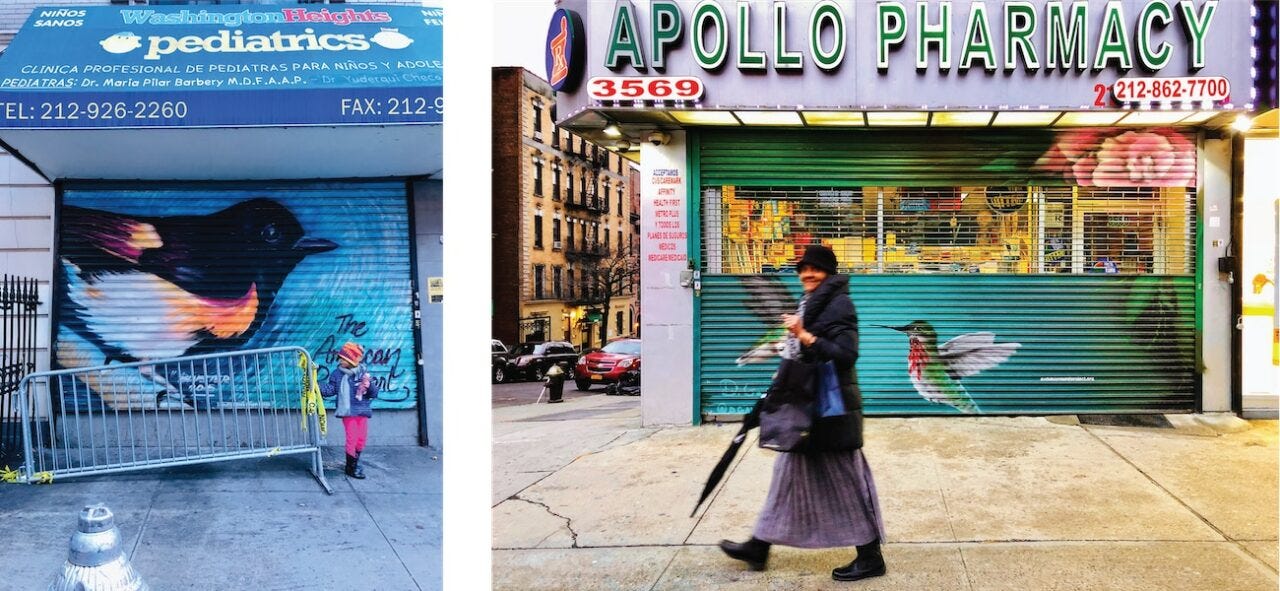

Both an essay collection and the best kind of miscellany, Lessons for Survival incorporates Raboteau’s photos of storefront bird murals alongside reportage, piercing and concise entries on conversations with friends about climate change over the course of a year, and candid essays about writing, mothering, and advocating for change in a small Manhattan apartment and then in a house in a Bronx with an unexpected and initially alarming pond that turns out to be part of one of the buried bodies of water on this land of the Lenape people that we call New York City. Lessons for Survival never loses focus on Raboteau’s children as the impetus for the work she’s doing now, but also scrupulously maintains their privacy. The book is candid and tenacious, infused with hope, commitment to community, and advocacy for the earth and social justice, while also calling out oppressive systems and hypocrisy. For Raboteau, community includes her neighbors, writers and other friends, Indigenous elders, and her own ancestors.

Some of my favorite writing in the book returns to the themes of family and belonging that she explored in Searching for Zion, now seen through the passing of decades and the passing of loved ones, and the wisdom of age. I asked Raboteau if she’d be willing to share a little bit about how her ancestors influenced her work, and she sent the photos and reflections below.

"My dad died over the course of me writing this book, and I was tasked with also writing his eulogy. That was one of the hardest things I've ever had to write because I needed it to land with several different people in the audience, including my kids. My stepmother decided to have an open casket. I knew that seeing his corpse might confuse or scare my kids. Death is scary and confusing! I wanted my kids to understand that their grandpa was being reborn as an ancestor. So I brought up all these photographs to the altar which had been meaningful to my dad--photos of our ancestors. He had what he called an ‘ancestor wall,’ where they hung. The oldest picture--of my great-grandfather, dates to the turn of the twentieth century. His mother was enslaved. At my dad's funeral, I named all the ancestors, to place him in this lineage, so that my kids would understand themselves to be part of that history, too.

After the funeral, I inherited the photos from the ancestor wall, and hung them up in my own writing room, where they watched over me finishing writing the book. I asked them for intercession and guidance whenever I experienced doubt. Knowing that they overcame so much helped me to move forward. The eponymous essay in the book, ‘Lessons in Survival’ is about how my grandmother, Mabel, brought my dad and my aunties North, fleeing Jim Crow after the murder of their father, my grandfather. The picture in the center of my ancestor wall is of her, holding my dad on her lap when he was about five. He looks so much like my younger son, it's both uncanny and reassuring at the same time."

I’m grateful to Raboteau for sharing so generously, and with so much hope and care, in her work, and also for these reflections and glimpses of her ancestors watching over her. I’d intended to send out this newsletter this late last month, but a family emergency intervened. The good news is that this dispatch is going out on the official Lessons for Survival publication day—so if you order a copy, and I hope you will, it will ship out to you right away.

Three other small notes:

This Thursday I’ll be speaking with Idra Novey at the paperback launch for her exemplary and acclaimed 2023 novel, Take What You Need, at Barnes & Noble on Atlantic Avenue. Brooklyn, 6:30 PM. (She reached out after my gushing in the last newsletter!)

Last I heard, my class in Miami this Saturday afternoon, Family Stories We (Tell Ourselves We) Can’t Tell, has a couple open spaces left. 1-3 PM, MDC Wolfson Campus, priced at $30 for accessibility. Holla 305, hope to see you.

I’m always and forever a night owl—an inheritance from my mom and her mom—and so it feels most honest to send this out to you in the middle of the night rather than scheduling it to go out in the morning.

I’m a night owl, too. There must’ve been one among my ancestors. Thanks for the intro to this fascinating author.

Thanks for introducing me to another writer with Mississippi roots who has a lot to say. Stunning insight by Emily about her father becoming an "ancestor." Loved the "ancestor wall" and plan to make one myself.