I first encountered Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s work in her engaging, quietly profound, and beautifully and wryly observed Letter From a Japanese Crematorium, written soon after her grandmother’s funeral. The cremation and memorial both took place at the Sōtō Buddhist Temple that’s been in the author’s family since her great-grandmother’s day. “My cousin Takahagi, a Buddhist priest, does not want me to go to the crematorium,” the essay begins. “It is not a place for visitors. When I press him, he explains: the crematorium is a gateway to the next world and is potentially dangerous…. the soul that is finally and forcibly removed from the flesh might snatch along a family member or friend for company.” As I think back on how many times I read this essay after it was published in 2007, I wonder about the seeds planted that ended up contributing to Ancestor Trouble.

I was also a fan of and loudmouthed advocate for Marie’s first novel, Picking Bones from Ash, published by Graywolf in 2009. As with the essay, the first sentence of the book is elegant and precise, deftly evoking the themes that will occupy the novel as a whole: “My mother always told me that there is only one way a woman can be truly safe in this world. And that is to be fiercely, inarguably and masterfully talented.” Amy Tan observed that Picking Bones from Ash shows how “the ghosts of our mothers are always with us.”

Marie continued to focus on ghosts and death after the tsunami that struck Fukushima Prefecture in 2011, killing 19,500 people by drowning and thousands more through the ensuing release of radiation from Daiichi nuclear power plant, 25 miles from her family’s temple. In the days that followed, she wrote a short, grief-stunned, characteristically evocative essay for the New York Times, focusing in part on her priest cousin’s determination to stay and comfort the community, to perform funeral rites for those whose family members’ bodies were recovered. Despite his resolve, the high radiation prevented their own family from burying Marie’s grandfather’s bones, and Marie found herself deep in mourning too over the unexpected death of her American father. All this loss and her journey to find solace became the subject of her second book, Where the Dead Pause and the Japanese Say Goodbye, published by Norton in 2015. The book is infused with sorrow but also spirit, acceptance, and understanding. And I have no doubt that Marie’s third book, American Harvest: God, Country, and Farming in the Heartland, is excellent and insightful, too. I’ve had a copy here since it was published in 2020, but I haven’t read it yet because in grappling with my evangelical Christian background and the ongoing connected dysfunctions in my family of origin, I just haven’t been in the right head or heart space to delve into it yet. But it’s here when I’m ready for it.

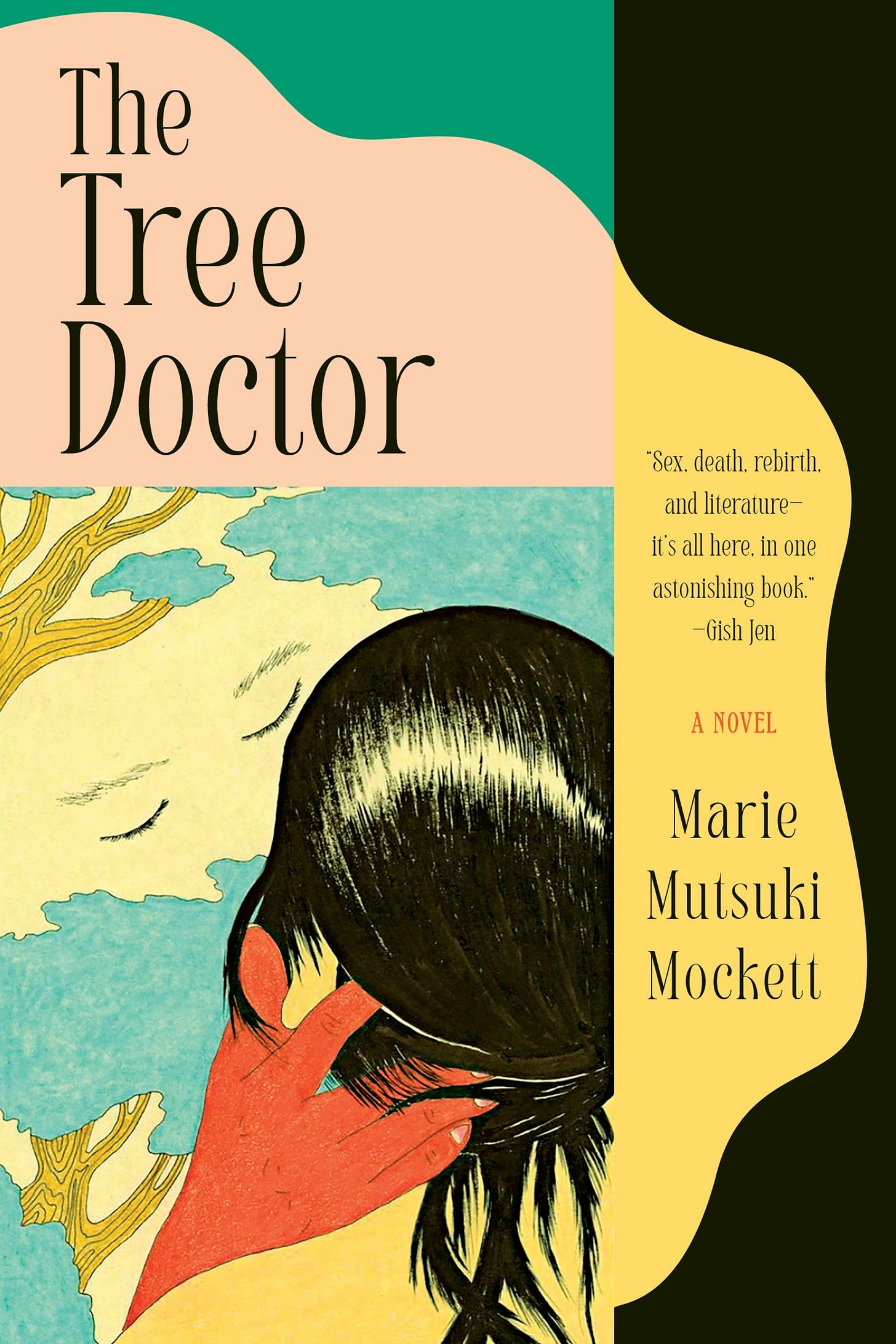

Her new novel, The Tree Doctor, is an absolute delight. It’s set in California during the pandemic, as the protagonist’s aging mother is admitted to a care facility and the protagonist becomes unexpectedly stuck in the U.S. rather than being able to travel back to Hong Kong, where her husband and children are living. From her childhood home in Carmel-by-the-Sea, the protagonist tends her parents’ garden, teaches The Tale of Genji to international students, and finds herself swept into a love affair (or at least a sex affair!) with a tree doctor after her mother’s gnarled cherry tree—called Einstein; a volunteer who took root unexpectedly, was tended lovingly, and flourished for decades—falls ill. The book is decidedly not autobiographical, and yet Marie has written about losing her own mother during the pandemic and facing Mother’s Day without her, so her own losses did feed the book. I don’t want to say too much about the plot and the philosophical and psychological threads woven together by the author in The Tree Doctor, but among other things I love that the cherry tree and garden more broadly are characters in their own right, that the interdependence of the human and beyond-human world come into focus with such a light twist of the viewfinder. I hope you’ll read the book and experience its delights for yourself.

I was curious whether Marie saw a throughline between her past work that’s more explicitly focused on ancestors, kinship, and ghosts, and this latest book. In response to my question, she was kind enough to send the following:

I have been mulling over this question of ancestors and its connection to my work ever since you posed it. First I thought: This book has nothing to do with ancestors. But of course this is patently untrue when I think about the fact that the narrator spends not an insignificant amount of time trying to wrangle The Tale of Genji, which comes to me through my ancestors. By this, I mean that, yes, the book is often considered the world’s first psychological novel and thus belongs to all of us, but at least to me personally, I know it as a text that is foundational to Japanese culture and aesthetics, and have often wondered what a close reading might reveal about Japan and thus my Japanese ancestors. Working through that text in conjunction with writing the novel did teach me a lot and also raised questions.

On a personal note, I have a couple very strange and spooky experiences in Japan that I felt even from childhood meant I was dealing with a very different mode of existence in Japan than when I was home in the US. I mean, I’ve been in the odd pub on the East Coast or even in the UK, and felt or heard strange sounds only to learn after the fact that these pubs and inns were considered haunted. In Japan, though, I had two very odd encounters that still gnaw at me, but when I read the Tale of Genji with its stories of ghosts and possessions and powerful spirits that don’t derive from Judeo-Christianity, I have a bit more context for what I experienced. The constant grounding of people’s emotions in Genji through poems and nature are directly and intentionally reflected in The Tree Doctor too. The other day, when I was visiting a book club, someone asked me why the book was called “The Tree Doctor” and not named after the female protagonist. Just as quickly, another reader pointed out that the tree doctor doesn’t have to be a person—it could be the tree itself, as in nature itself had helped the protagonist. This is how I read the title. And Genji is threaded with people expressing themselves through plants and flowers and even, occasionally, through trees. So there is some ancestor magic at work.

Genji is also full of sex—and so is The Tree Doctor. I've known for a long time that the indigenous religion in Japan is "nature worship." Setting aside how precise this phrase is—scholars argue—this nature worship is most definitely not Judeo Christian. We would classify it as animism. If you go far back enough, probably none of our cultures were Judeo Christian with gods who looked like men and spoke to us—they were animistic in nature. And it's impossible to avoid that sex is a part of nature and the sexual drive is a huge force. The Tree Doctor also assumes that what is sexual is existential. Yes, I mean that sex is necessary for human procreation and survival, but it also speaks to us about who we are. I think that sex speaks to all of us at all stages of life, a fact that becomes complicated when we aren't just sequestering sex to orientation, sin (not really an animistic attitude but a Judeo Christian one) and procreation. What else does sex tell us? I think whatever it tells us comes from some larger force, yes, but also directly from the ancestors who made us and gave us our DNA.

I was raised to always respect the ancestors. The funny thing is, I didn’t even know I was being raised this way, as no one said: “Respect your ancestors.” It was more the case that when I went to Japan, I immediately visited altars in people’s homes, and was taught to give special foods to the ancestors before I ate it (like a basket of fruit or packet of cookies). Now that my mother is buried in Japan, I am compelled to go and visit her. She set things up that way. She made sure she would be buried there so I would feel free to go to Japan and feel it is still my home. For me, feeling the presence of ancestors is always physical, and I didn’t even realize, when small, that this knowledge was being transmitted. There were a great many things my mother did to make clear to me what care for family and ancestors looks like. She always had my room ready, for example. And to a certain kind of American, this might look like coddling or a constant assertion of her motherhood. I see she just wanted me to understand I always had a place.

As for how this impacts The Tree Doctor, it is hard to say. There have been many days when I think about all the ancestors and feel I have failed them. Many days I just ask for their protection and help so I can do better. I explain that I am a person who is part of them (Japanese) and part something else (Anglo-European) and that I am always trying to navigate this gap in ways that I can’t always see. I also know that when I move around in an American space, the fact of my constant translation isn’t apparent. I know the ancestors would be asking me mostly to be a good and productive person and likely also to be true to some inner voice—so I try. I often feel that I am failing.

The Tree Doctor ends with a few notes on what it means to be part of a family. I think probably most every Asian American person understands what it means to feel intense pressure to be part of a family, preserve a family and take care of a family. Doing this is part of how the ancestors are protected. But as an American, my understanding of family is perhaps more expansive—you can be family with people who are not blood relatives. I also realize as I get older the conflict I feel between always trying to care for the family/ancestors and the impulse of the individual.

Without giving away too much, the protagonist at the end of The Tree Doctor makes some decisions that I think are a blend of taking care of both family and self—a blend of what the ancestors might want and what she as an individual can do in America which prizes the individual above all--at least, as I see it, compared to Japan where I have been living for two years.

I’ll be back before long, or at least that’s my intention. I know better than to promise by now. Prior installments in this series, in case you missed them:

Thanks for the recommendation📚

Thank you for this! Marie Mutsuki Mockett is a revelation. She is such a gifted writer.